Over the previous five or six years,

he had optimistically participated in

just about every significant collabora-

tion organized to make Memphis and

Shelby County bike friendly. In 2003, for

example, he joined a bicycle/pedestrian

advisory committee convened by the

city’s metropolitan planning organization.

In 2007, he was part of a community-

rallying effort named Greening Greater

Memphis. And earlier in 2008, Siracusa

had joined a range of environmen-

tally minded individuals in an ongoing

effort to hammer out what became the

Sustainable Shelby Plan.

Each round generated smart ideas,

encouraged valuable alliances and stirred

enthusiasm, he recalls. But when 2008

rolled around, Memphis still had no

bike lanes. And

Bicycling

magazine had

just named the city one of the nation’s

worst for cycling, a nod to be repeated in

mid-2010.

The two lanes under discussion were

indeed painted in fall 2008 and her-

alded as the first of many. Still, Siracusa

says there was little widespread faith that

a truly navigable network would fol-

low. City leadership at the time admit-

ted Memphis was “behind the curve” on

bike lanes, but gave reasons for the delay

that rang hollow to active-transportation

advocates. For example, one reason cited

was a desire to replace stormwater grates

first; the grates in use had grooves that ran

parallel to curbs—grooves that bike tires

might get stuck in, causing wrecks and

lawsuits, or so went the explanation.

“It was farcical, obstinance at its best,”

Siracusa says. “So you have to understand

that in 2008 we had nothing; we literally

had nothing to lose.”

Then came the Shelby Farms Greenline.

An Alternative Route

It may have appeared to some that people

pushing for bike lanes were spinning

their wheels—that they were a politically

inconsequential fringe element.

But among that mobilizing fringe was

a group drawing inspiration from success-

ful rail-trail conversions across the country.

Dubbed the Greater Memphis Greenline

(

greatermemphisgreenline.com

),

the group took a keen interest in a

disused CSX railway corridor that

stretched from the inner city east-

ward under Interstate 240, over the

Wolf River and into the 4,500-acre

Shelby Farms Park.

Hmm. Maybe the local path to

active transportation could start

slightly off-road.

The idea was radical for the place

and time, but the group latched

on and didn’t let go. As Founding

President Bob Schreiber puts it, “We

just started jumping up and down

and yelling and screaming.”

He chuckles as he says that.

Tactics were actually quite civilized.

Group leaders held monthly meet-

ings in Schreiber’s living room,

booked themselves as presenters

before any organization with ears,

and set up booths at community events

to hand out research results, sell hats and

T-shirts and start conversations.

Bit by bit, support grew. One very good

day, it grew a lot.

A group of anonymous donors stepped

up with most of the roughly $5 million

that would ultimately buy enough of the

corridor for a 6.5-mile trail. One donor

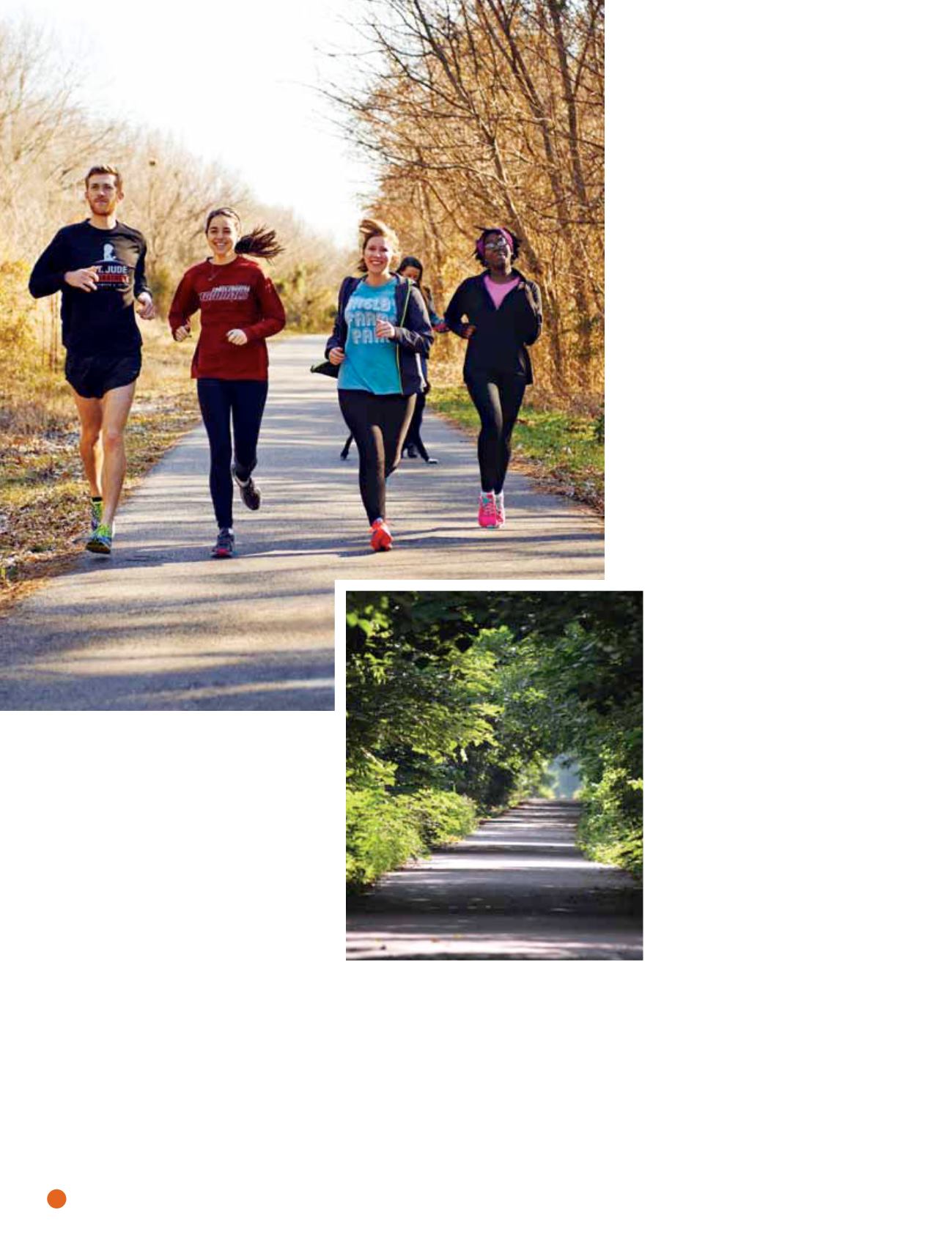

Phillip Parker/AP Images

courtesy shelby farms park conservancy

Left: John Grisham, Hilary Quirk, Rebecca

Dailey, Betsy Peterson and Chelsey McKinney

on the Waring Road to Perkins Road section of

the Shelby Farms Greenline

The Shelby

Farms Greenline

has become

a valued

recreation and

transportation

amenity for

Memphians of

all ages.

rails

to

trails

u

spring/summer.15

10