finally connected—creating one of the

longest rail-trails in the country. If you

had told me 30 years ago that a 94.5-mile

trail connecting Anniston, Alabama, with

Smyrna, Georgia, would have been pos-

sible, I wouldn’t have believed it.

What were some barriers that

impeded Southern rail-trail develop-

ment historically?

The first barrier was lack of familiarity.

There simply weren’t that many rail-trails,

and we had to explain to people what they

were and their value. Another huge hurdle

was people’s hesitations about having

trail users riding and walking so close to

their property. Some adjacent landowners

thought that once the railroads closed, the

land would automatically revert back to

them, which wasn’t necessarily the case.

Historically, the South has not been a

place with a lot of public amenities. The

states haven’t had much money to spare

over the course of their development—and

some people questioned whether or not

rail-trail development was the best way to

spend limited public dollars.

But an important strategy for successful

rail-trail development is choosing targets

of opportunity. You focus on those that

are going to get you the best play, the best

exposure … places that are central to the

thinking in a state. That’s what made the

Silver Comet Trail—which is located just

outside of Atlanta, Georgia’s state capi-

tal—such an important early target. And

knowing that the Chief Ladiga was being

developed, and that it could meet with the

Silver Comet at the state border to create a

continuous system, was very compelling.

How did you manage to generate

public support?

I made the most of the few wonder-

ful trail examples we did have in the

South, such as the Virginia Creeper and

W&OD. They became my models, and

we organized trips so people could visit

and experience them for themselves.

Another very important tactic was

gaining support from key local influenc-

ers—people who were recognized for

their wisdom or leadership. And most

of the local leaders really “got it.” They

were active citizens and professionals

that felt rail-trails were needed in their

communities.

After you got the support, were there

any other major roadblocks? And how

did you manage success?

Once we managed to generate public sup-

port—a major roadblock was the lack of

available funding to support the rail-trail

projects. This was true for the South more

than for any other region in the U.S.

After about two years, I was promoted

to government affairs manager, and my

work took a new focus: advocating for

federal trail funding. My aid for the South

became indirect, but we knew if rail-

trails were going to be successful in the

U.S., and in the South in particular, there

needed to be a steady flow of money avail-

able for communities—a source of fund-

ing that was dedicated to these types of

projects.

The nation’s first trail funding in the

federal transportation bill was introduced

1991, and over the past 25 years, we’ve

worked hard to try and grow these funding

sources and defend them from attack.

It really took that kind of kindling to

light a fire for the southern movement,

because there were so few other funding

sources available for trails there. At first the

momentum was slow, but rail-trails started

to come and then kept coming. Now we

have so many great national examples like

the Medical Mile in Arkansas, the first

rail-trail in the country a medical com-

munity took responsibility for to promote

local health, or the Pinellas Trail in Florida,

which became a national example of how

trails can create safe walking and biking

connections in busy urban areas.

Up until a generation ago, almost every

southerner had a farm in the family and

maintained ties to a more rural way of life.

For many southerners living in an urban

context now, rail-trails are a new way to

reconnect with the outdoors. As gen-

erations pass—trails are becoming more

important.

Then what happened?

Around the same time, I had also got-

ten involved in the transformation of

a disused corridor in Georgia, running

from Rockmart to a place no one on the

organizing committee had ever heard

of, which the paperwork called Etna.

We couldn’t find it on a map. One rainy

afternoon, a local organizer, Brenda

Burnett, and I had the Georgia state trails

coordinator drop us off where we thought

Etna would be, and then we trudged

along the corridor through the Georgia

mud searching for it. Unfortunately, it

started to storm even harder, and we were

almost blinded by the rain. We almost

missed Etna—which it turned out was

just a gray utility box with the letters

“Etna” stenciled on it. That corridor

became the Silver Comet Trail.

The Georgia Rails Into Trails Society

[GRITS] became very active, and

we went through the process of con-

vincing the Georgia Department of

Transportation to put the corridor into

public ownership.

The first section of the Chief Ladiga

opened in the mid-1990s, and the first

section of the Silver Comet opened in

1998. In 2008, the completed trails were

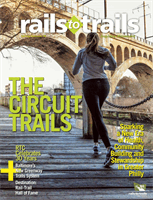

Fowler on the Mount Vernon Trail

in Northern Virginia

ELI GRIFFEN

rails

to

trails

u

spring/summer.16

19